Gregorian paleographic research in Hungary ↘

About the Project

The Hungarian Neume Catalogue – Notation Signs in Medieval Hungary is an online website presenting the basic elements of chant notations of old manuscripts (codices and codex fragments) from the territory of medieval Hungary. When we started desig ning the site, two goals were set. First, we wanted to investigate all plainchant notations from the Hungarian Middle Ages that fit under the umbrella-term “Esztergom notation”, and to show all the characteristic components of these writings in an online database compiled on the basis of a homogeneous series of criteria, presenting the details systematically to the researchers of interest and the public. Secondly, our aim was also to create an online interface, which can compare different musical writing signs (“neumes”) lurking in sources from medieval Hungary – mapping, separating and characterizing the writing traditions based on the analogies revealed during the comparison.

The plan of an online neume catalogue dates back to a few years. Its preparatory work was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Gothic Music Notations in Hungary in the Light of Plainchant Sources from Central Europe), won by Gabriella Gilányi in 2016. The research did not stop even after the project had been completed, in fact, it expanded further with the experience we had gained in music paleographical examination of codex fragments over the past few years. The dynamically developing musical fragmentology research in Hungary and abroad has multiplied the number of sources to be studied. Many new folios or part of folios representing an individual codex could be analyzed, which opened up new perspectives for research. Currently, the activities of the ՙMomentum’ Digital Music Fragmentology Research Group include music fragment studies and paleographic analysis as well, which has offered an opportunity to implement our long-cherished plan of a digital Hungarian neume collection.

Janka Szendrei's pioneering monograph dealing with Esztergom notation (Középkori hangjegyírások Magyarországon [Medieval Notations in Hungary]. Studies on Hungarian Music History 4. Budapest: Institute of Musicology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1983) is an indispensable work for Hungarian music paleographic research, but developments in the digital era now offer new research opportunities to be exploited. Today, we have come to the point where the content of a medieval source can be conveyed more and more directly and more publicly with the help of modern tools. Small digital photo excerpts can be compiled into online surfaces and databases, containing every little detail. The data in these systems – similarly to other digital collections - is searchable and comparable. Based on certain aspects, all our sources and chant notations can be incorporated into such a system, and the emerging matches can be used to identify the musical writing types, and, among others, the provenance of newly discovered sources.

The online catalogue focuses on the actual forms of the neumes as they can be found in the sources, thus bringing to life both the manuscripts’ musical elements and full neume sets. At the same time, the website not only makes musical signs visible, searchable and comparable, but also performs most of the scientific evaluation: the categorization and identification of the musical writings. In this way, many chronological and geographical variants can be distinguished: the system is definitely able to capture and show this diversity.

The digital neume repertory is constantly expanding. The processing focuses on ՙHungaricum’ sources, the works of inland scriptoria in the territory of the medieval Regnum Hungariae. Not only pure forms of the Esztergom notation appear, but also its local variants and its late medieval musical writings of a more international character. Basically, all those manuscripts are included into the system, which can preserve any traditional writing element between the 12th and 16th centuries (up to the 18th century in the case of the retrospective sources).

The website is expected to be of interest not only to professionals, but also the wider public. By displaying the different chronological, geographical and institutional layers of the musical literacy of the Hungarian Middle Ages, the neume catalogue sheds light on the medieval copying workshops hidden from uninitiated eyes, where the scriptors and notators of Hungary wielded their pen tirelessly.

Gregorian paleographic research in Hungary

Gregorian paleographic research, i. e. the study of chant notations of medieval codices looks back on a hundred-year history in Hungary. The beginnings trace back to the works of Kálmán Isoz (1922: Latin music paleography), Zoltán Falvy in the 1950s (1954: “The Musical Paleography of the Pray Codex”) and then in the 1960s, to the studies of Kilián Szigeti.

The systematic and regular inspections of Hungarian chant notations launched in the 1970s, in parallel with the exploration of the Hungarian source material by Benjamin Rajeczky, László Dobszay and, above all, Janka Szendrei. The idea of producing a Hungarian notation history on the basis of the collected source repertory arose during the categorization and catalogization of the approximately 1454 Hungarian musical manuscripts gathered that time – they include complete codices, codex fragments, late medieval/early modern musical inscriptions, chant collections and retrospective manuscripts (see Janka Szendrei: The Musical Sources of the Hungarian Middle Ages. Studies for Hungarian Music History 1. Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1981). Szendrei’s systematic analysis on the musical scripts progressed source by source, and finally culminated in a monograph including all her new results, among which the discovery of the Hungarian, or so-called “Esztergom notation” could be considered the most significant recognition (1983: Musical Notations in Hungary in the Middle Ages, in German: Die Geschichte der Graner Choralnotation, Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungariae 30, 1988, Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest). This work about the history of Gregorian paleography is still a point of reference for the Hungarian and international plainchant research communities, and even for scholars coming from the direction of associate disciplines of the medieval studies. Szendrei guides us with punctilious thoroughness through the musical script versions of the most important ecclesiastical institutions of medieval Hungary. Our neume catalogue follows in Janka Szendrei’s footsteps, and attempts to differentiate the notations in more detail, as well as to present the complete collection of the basic neume signs from all surviving domestic sources of Esztergom notation. The project invites you to compare data interactively. It focuses on the source and its characteristic set of notes, in a way that also enables immediate comparison of a given element. The website guides the curious visitors into the world of Hungarian notation types, its institutions, eras, providing data not only to specialists, but also to the general public interested in medieval musical literacy.

What is a neume?

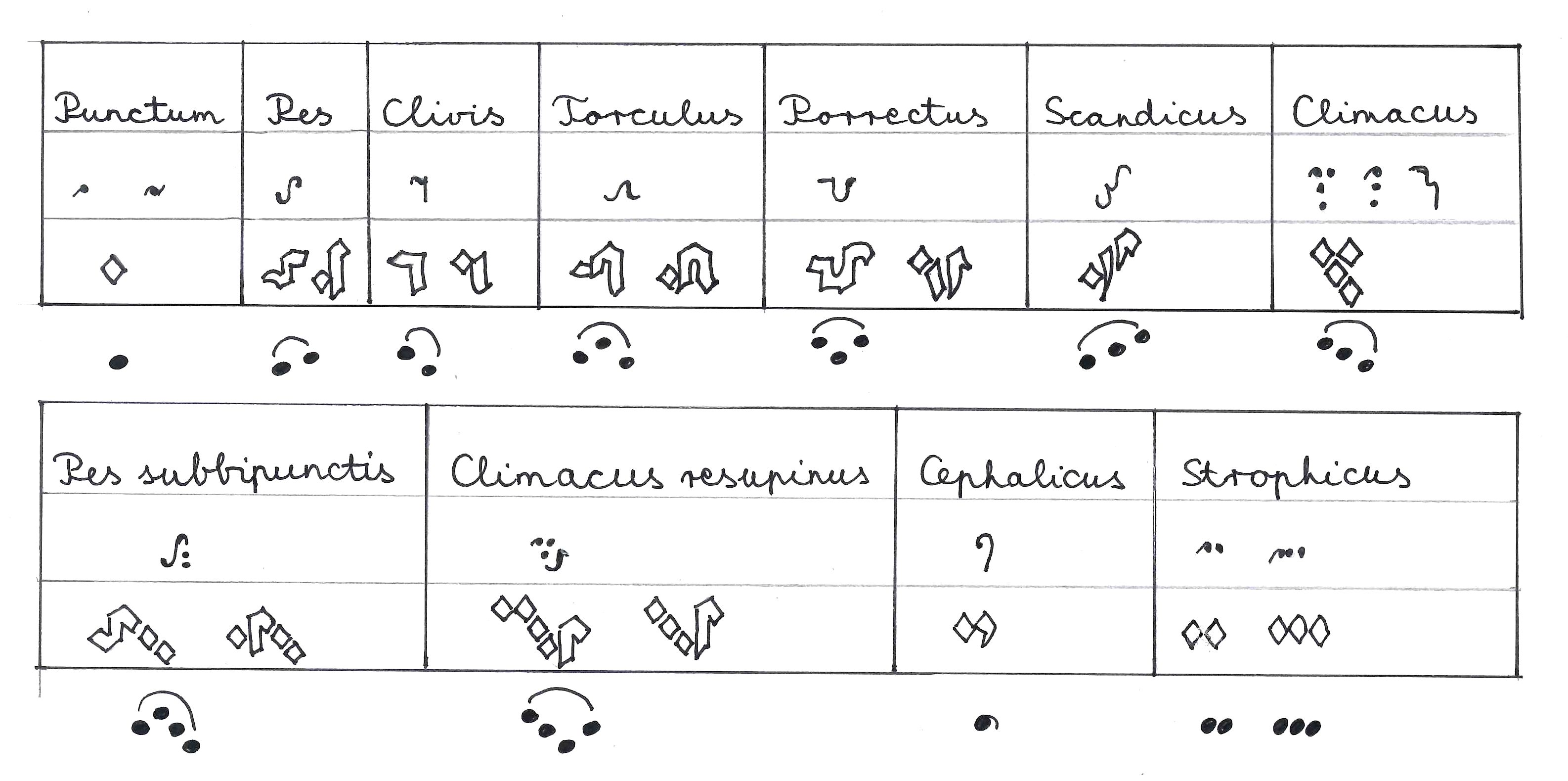

To interpret the parts of the website, first the terminology needs to be clarified. We call neuma (from the Greek ՙpneuma’, meaning ՙbreath’, ՙsign’, ՙmovement’, ՙgesture’, other medieval names are ՙnota’, ՙnotula’) the basic elements of the plainchant melodies, or the signs of the musical scripts, whose denotations have survived through theoretical works of the Middle Ages. In fact, neumes are tiny musical structures. The basic set consists of eight signs in the early manusripts (i.e., punctum, virga, pes, clivis, torculus, porrectus, scandicus, climacus, see Table below). These musical structures can be documented with unchanged meaning from all chant sources of the Middle Ages. The formation of the neumes was related to the Frankish-Roman liturgical reform of the 8th–9th centuries, borrowing several elements from the ancient (Roman and Greek) prosodic, ecphonetic signs, Byzantine music notation, or the drawing of movement of the conducting hands. Although the first sources with music notation from the last third of the 9th century use neumes only sporadically and incidentally, the complete musical codices contain a developed set of symbols, which have survived from the 10th century in different shapes, depending on local customs, institutions.

So, neumes are musical units of one, two, or three notes, the formation and use of which are inseparable from the first artwork of music history, the plainchant. Belonging to the primary corpus of this musical repertory and conceiving in oral culture, the melodies cannot be interpreted as a series of notes, as in the later styles of music history. The Gregorian chants consist of musical gestures and formulas, and they have been recorded in a special way: the neumes indicate the number of notes making up the neumes, as well as a certain pitch relation inside the sign. The names of neumes may capture a moment from the elementary progress of the melody (e.g. the climacus is ՙladder’, a descending group of notes, the torculus is ՙtwisted’, i.e. notes up and down, the porrectus is just the opposite: it ՙstretches’, ՙextends’ the punctum up and down).

The names and form variants of the basic neumes in the Esztergom and the Messine-German-Hungarian Gothic notations; their transcription

In early times, neumes indicated only the number of the notes that built them up and the directions of the steps, not the pitches themselves. Although their origin had faded away, the most common theory regarding their roots was that neumes followed the movement of the conducting hand (see theory of cheironomy). The music script did not yet indicate exact pitch, it was adiastematic. Beside the basic neumes, Gregorian chants were originally written down onto parchment with a number of additional signs: the most sophisticated and diverse set of symbols appear in the early St Gallen notation. We do not know what kind of performance was indicated by these special neumes that appear here, how exactly the trigon, quilisma, oriscus had to be sung. Most of the additional signs were later discarded, the complex forms were simplified, and their meaning was lost. Very few of them were included in the later Hungarian/Esztergom notation, the script of which was already born on staves. In Hungarian notations, there were no additional or modifying signs outside the cephalicus (Greek kephalis = head), strophicus (= a sound that had to be repeated several times), and the so-called liquescent neumes that had been added to the normal signs as a drop form, mostly indicating a subtle nuance related to text pronunciation (see con -va-lem, ad-mi- ran -tes).

Medieval tables also contained some neume combinations, so-called ligatures, in which more than three notes (4–6) were linked. E.g. a porrectus flexus meant “turn down” that is, three notes are joined by a fourth, lower step. Torculus resupinus, on the other hand, meant “turn upwards”: this torculus + punctum sctructure referred to the unity of a torculus and one more note, rising a note higher than the last one of the basic neume.

Based on our new neume catalogue, one can get an overall impression of the most important neume combinations found in Hungarian chant sources. Although these combinations are varied in a way typical of the source, the same selection in our system cannot always be displayed in the prevalent lack of a neume combination in the given musical scripts (especially in the case of codex fragments). Nonetheless, we tried to maintain a unified design by starting this series of such ligatures with the forms of climacus resupinus, if they occur in the manuscript.

Additional elements of the notation are the staves, the bounding lines, the clefs and the custos signs at the end of a staff indicating the pitch of the next line. We believe that these details of the musical writing may also be important in the characterization of a notation, so they are included in our system, making them searcheable and comparable.

The notation of the Gregorian manuscripts is also determined by different variants and writing methods of the basic neumes and their combinations. The formation of the elements (e.g. conjunct or disjunct, vertical or diagonal, rounded or gothicizing in their design, small or large) are traditional or even workshop-specific characteristics that may vary from source to source. While the common features indicate chronological or geographical analogies – the correspondence of neume sets is an important key to the identification of the notation and through this, the source itself –, differences can be used to compare distant inland subtraditions.

Hungarian notations

The Esztergom notation (13th–14th centuries)

The first surviving manuscripts with music notation in Hungary (at the end of the 11th century) were written in German adiastematic neumes in campo aperto, in the empty space between the text lines. These notations did not indicate the pitch, so they were unsuitable for singing from them, hence the reconstruction of the melodies is not possible either. The early 12th-century notation above the text of the Luke's Genealogy of the Hartvik Agenda (= Chartvirgus-pontificale, HR-Zmk MR 165) contains some musical signs (e.g. a vertical climacus starting with two points, s-shaped pes, 9-shaped cephalicus) that reveal the intention to create a new neume system, which could already be explicitly related to the later Esztergom notation. A more or less developed staff notation can be documented a few decades later, from the middle of the 12th century, in fragments preserved in Krakow (cover page of PL-Kj Ms. 2372, middle of the 12th century) and Šibenik (HR-Ši Cod. 10), and in the Pray Codex (H-Bn Mny 1), which had been written around 1192–1195. These manuscripts consist of a special selection of neumes, a special compound of elements, which, as an independent system, is included exclusively in the codices from medieval Hungary. As such notation cannot be detected outside Hungary, its application always refers to Hungarian provenance, just as its development ‒ together with the rite of Esztergom ‒ certainly took place in the Hungarian archbishop's seat, Esztergom, at the end of the 12th century. The carefully selected neume set of the Esztergom notation, its proportional, elegantly flexible appearance evokes German influence and a strong Latinization at the same time, as a result of the reception of German, Frech, Messine and Italian writing elements.

Besides the special writing direction ↗↓, Esztergom notation can usually be identified by a set of unique elements (see table below): Messine tractulus-like punctum (“fly-foot shape”) with thin introductory and ending lines, rounded pes, right-angled clivis (Messine type), round, conjunct torculus and porrectus, conjunct scandicus (similar to the beneventan gradata), vertical climacus with double points (see the old Messine form of the neume and the northern Italian parallels), a subordinate conjunct form of the latter and the Messine cephalicus.

|

|

Punctum |

Pes |

Clivis |

Torculus |

Porrectus |

Scandicus |

Climacus |

|

Missale Notatum Strigoniense, 14/1 SK-Bra EC Lad.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Janka Szendrei’s opinion, the indirect evidence and foreign analogies suggest that a group of progressive music theorists in Esztergom may have developed a new staff notation within the framework of a general liturgical reform. This work can be traced back to the reign of King Béla III and Archbishop Lukács Bánfi (the latter one studied in Paris in the second half of the 12th century). Lukács and his school-mate, the papal legate, Job, could not only supervise the reform, but through their contribution, the reformed Ritus Strigoniensis as well as the new Hungarian chant notation could become the norm to be followed throughout the Hungarian churches.

The last phase of formation of the Esztergom notation – a neume set, which has been christallized by the end of the 12th century and then further elaborated in the 13th century – gained its final form under the last ruler of the Árpád dinasty, the Venetian-born Andrew III. After the extinction of his dinasty by the first third of the 14th century, the former angular Messine structures were transformed into Italian roundness, which again indicates some change in the foreign relations of Hungary. The notation of Esztergom in the 14th century, this exceptionally elegant, sophisticated, flexible and proportionate music script, developed into one of the most aesthetic chant notations in Europe during the reign of the Capetian House of Anjou kings.

Messine-German-Hungarian Gothic notation (15th–16th centuries)

The 14th–15th centuries became a period of functional change of plainchant codices, giving free vent to a new notation fashion. The enlarged, more representative choral books served as accessories of everyday liturgical practice: the late medieval church choir sang from a monumental manuscript, which was placed on a stand during the liturgy. Because these luxury codices contained large letters and musical notes to sing from, the formerly flexible Esztergom shapes of neumes were replaced by rigidly broken, increasingly articulated Gothic writing elements. The grandiose scale, the standardism and the precise sizing all improved the readibility. This change of function could be realized by adopting the Gothic technique of pen treatment, which gradually brought the areas east of the Rhine under its influence, and, similarly to the beginnings of our notation history, once again set the further development of the Hungarian notation on a given path. Thanks to the special cut of the feather, large neumes could be written by alternating thick and thin elements: this gave a special rhythm to the script. After arriving in Central Europe, the Gothic writing style easily mixed with the earlier neume structures, so the previous tradition could be incorporated into the new professional chant notation, which was presumably created in the copying workshops of Esztergom–Buda. Besides the main type of this new Esztergom notation, local variants have been cultivated in significant rural centres (eg. Trnava, Bratislava, Spiš) – a future study can undertake to separate these subtraditions.

The mixture of neumes, which had been created from earlier and later elements, was a product of Hungarian workshops as well as in the case of the earlier calligraphic Esztergom notation. Due to the high quality of its execution, it can also be correlated to the emblematic Hungarian chant script of the previous period. What the two have in common is that they could have been created for foreign inspiration after careful planning in the Hungarian church centre, then further developing in local copying workshops. At the same time, the range of the use of late monumental music script may have been narrower than that of the classical Esztergom notation, mainly for material reasons. In addition to the country's central churches in Esztergom–Buda, expensive deluxe codices could only be afforded by episcopal seats and major wealthy chapters/parish churches, and this particular mixed notation was still shared in practice there with the expansive Messine German Gothic notation, above all in the cosmopolitaner towns of the peripheries of Hungary. There were some Esztergom characteristics in this modern notation, e.g. the unique form of the early conjunct scandicus (see below), which can be considered an inherited neume instead of the Messine–German structure of two punctum + virga. The writing direction of climacus, at the same time, changed since the 14th century compared to the early Esztergom tradition, the puncta below each other slanting to the right and not placed vertically due to the increase in the size of the notes. Its peculiarity is that it begins with a single punctum or more traditionally, like in Esztergom formerly, with a double note. The conjunct form of the same sign is also a remnant, similarly to the conjunct pes, torculus, porrectus, and their combinations (its proportion varies from source to source, formulating more and more articulated in the chronology, see below). The design of the folios is typical: staves of the four red lines, double c–f keys, pipe-shaped custos.

|

Punctum |

Pes |

Clivis |

Torculus |

Porrectus |

Scandicus |

Climacus |

Combinations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As a common feature of the modern Gothic neumes, suitable for writing these large books and also their 14th century antecedents, both were influenced by contemporary Messine notation. But while the former was touched by its earlier, purer form, the late Hungarian version followed a Messine–German Gothic mixture as its pattern.

Traditional Hungarian notations

The treasure trove of Hungarian paleographic research is the notation of the late medieval (15th–16th -century) peripheral sources (mainly from the Northeast Hungary and Transylvania): their varied music scripts could be considered as traditional Hungarian notations. Mainly financial reasons laid behind the traditionalism, as these poorer institutions of lower rank could not afford magnificent, ornate codices. Conservative workshops kept cultivating the earlier notation of Esztergom, the script of which was established and became the norm in the Hungarian church by the 13th century, some others (e.g. in Transylvania) followed the more calligraphic, rounded variant of the 14th -century Esztergom type. Later the early elegant neumes were enlarged and thickened according to the new pen treatment fashion, then the the elements were separated within the neumes to make the notes fit better on the staves.

It is characteristic of several of these local versions that the usually non-professional notators placed them on the parchment with the ease and simplicity of the cursive notation. There is an enormous difference in how many modern elements enrich the local traditions, or how much space they have left to let in new influences. The most elaborate and conservative system has undoubtedly been related to the late medieval Pauline fathers (the only order founded in Hungary), who preserved the 14th-century notation tradition of Esztergom in an era when Esztergom gave up its own tradition for moving to a more modern, international path.

The Northern and Eastern Hungarian scriptoria need to be mentioned here, however, the investigations have only recently begun to describe them. In our system, “late Esztergom notations” mean music scripts which belong to the traditional group of notations, secondarily we specify the subtype, e.g. North-Hungarian, Transylvanian, Pauline.

Late Esztergom notation (Pauline)

|

Punctum |

Pes |

Clivis |

Torculus |

Porrectus |

Scandicus |

Climacus |

Combinations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Late Esztergom notation (Transylvanian)

|

Punctum |

Pes |

Clivis |

Torculus |

Porrectus |

Scandicus |

Climacus |

Combinations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We also have to mention the so-called cursive notation practice of Esztergom, a practical shorthand, taught in the schools of late medieval Hungarian ecclesiastical institutions (see Archbishop Tamás Szalkai's school notes from 1490, Esztergom Cathedral Library, Ms. II. 395). This cursive notation appearing in late medieval sources bears witness to a generally high standard of medieval musical literacy in Hungary, and it was the type of notation that transmitted the medieval liturgical musical tradition to the period after 1526.

Cursive Esztergom notation (16th century)

|

Punctum |

Pes |

Clivis |

Torculus |

Porrectus |

Scandicus |

Climacus |

Combinations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|